Just listened to this story again via the Church Basement Roadshow. It’s a great reminder of those we’re called to serve and love.

Take some time to read it, or enjoy Mark’s reading of it via the Church Basement Roadshow.

Love those who least expect it and love those who least deserve it.

SOUL GRAFFITI

Chapter Four: Experiments in Truth

By Mark Scandrette

It is bittersweet to recall the first few years that our family lived in San Francisco. We had moved to the city with a dream: to form a community of people who would take Jesus seriously as the teacher and revolutionary he intended to be. Our new neighbors and acquaintances were quick to point out that people who called themselves “Christians†were responsible for the inquisitions, religious wars, and homophobia—not to mention the historic use of scripture to justify slavery, the massacre of native peoples, aggressive foreign policy, and the destruction of the Earth’s resources. I had to agree that there was tremendous dissonance between the dominant reputation of Christianity and the life of Christ and the early church. We desperately wanted to be people who embodied the revolution of the kingdom of love—offering an apologetic for the authenticity of the Way of Jesus as an alternative to mainstream Christianity.

A small group of us began meeting together to study the gospel accounts and the documents of the early church. We were drawn to the communal nature of the primitive church and the power, solidarity, and compassion followers of Jesus exhibited under persecution during the Roman Empire. Our faith community, which at the time we called a house church, attracted zealous idealists as well as people who had been hurt or marginalized through their experiences with organized religion. For a while we felt criticized and misunderstood, both by the culture and by the mainstream church. It took some time to move beyond critical deconstruction—to define ourselves more by what we were for than what we were against.

Gradually we learned to channel our group energy toward experimenting with how to imitate the path of Jesus and the early disciples. Some things we took quite literally. We tried fasting and praying for forty days. I grew a beard and long hair. We began living communally. And we hosted parties for neighbors and offered hospitality and friendship to people battling addictions, personality disorders, and depression. It was, in retrospect, a fertile and chaotic period for our family. We were being formed through these experiences with great intensity. One thing we try to preserve from that time is a sense of humility and risk taking.

We found that one of the best ways for our group to learn the Way of Jesus was by trying to imitate his example through some tangible exercise or activity. Mahatma Gandhi described this kind of intentional pursuit as an “experiment in truth.†Experiments are always successful on some level, because by taking a risk you learn both from your failures and accomplishments. And there is a depth of understanding that can only be achieved through conscious activity.

It is my hope with this book not only to explore ideas about making a life in the Way of Jesus, but also to share some of our family and community “experiments in truth.â€

Emperor Arcadia

After reading about the kind of companion Jesus was, and knowing what he taught about love for neighbors, my friend Joseph and I decided to try some experiments in radical openness to people. We began by making a daily practice of picking up trash on our block. In the evenings, along with my kids, we walked around the block with trash sticks and plastic bags greeting neighbors and collecting debris. The sidewalks in our neighborhood were notoriously dirty, strewn with household garbage, old couches, bed frames, and broken TVs. People’s reactions to our nightly trash walks varied. One person offered us cold beers. Another asked us to pray for his family. One neighbor thanked us for our kindness and another cussed us out because he thought our clean-up was a manifestation of privilege and gentrification. What we hoped would be a sign of neighborly affection was interpreted ambiguously.

After a few months of picking up garbage we prayed that God would bring someone into our path that we could care for more deeply. Riding the bus home from work one night, Joseph met an elderly man who seemed lonely and in need of a friend. He invited Joseph to visit and the next day Joseph took me along to see him.

“Come on in, boys. Will you smoke a joint with me?†the old man said as Joseph and I climbed the steps of the rusty old school bus, searching for a place to sit. The bus, parked in a vacant lot on Portrero Hill, was painted in bold letters that read: “I HAVE BEEN CONDUCTING EXPERIMENTS ON MYSELF FOR 30 YEARS—EXPLORING THE MYSTERIES OF CHEMISTRY AND HEALTH. MY PRESCRIPTION: EAT A CLOVE OF GARLIC AND DRINK YOUR OWN URINE AND SEMEN TWICE A DAY.†Joseph and I glanced at each other and wondered what we were getting ourselves into. Shaking my hand, the small old man, wearing a black evening gown, took a bow saying, “You may call me Emperor Arcadia.†Seated again, his arthritic hands struggled to roll a joint while he spoke. “I’ve been taking speed for thirty years, medicating myself. The combination of speed and special topical chemicals is curing me of all human diseases.†As he continued we stole glances around the crowded old bus containing soiled clothes, salvaged computer monitors, and buckets of urine. A mix of curious smells strained my nose for recognition.

“The government has lied to us! It’s a conspiracy to exterminate the planet! If I were in charge I would burn all the money and declare the planet monetary and class free. We will all be equal and wealthy.â€

I attempted to break into his monologue with a question: “Emperor, how long have you lived in San Francisco?â€

He quickly replied, “Too long. Do you have an estate in the country where you would like me to be the caretaker?â€

I tried again: “How old are you?â€

He quickly answered, “I’m not old, I’m as young as they come.â€

I persisted, “Where did you grow up?â€

“Grow up? I haven’t grown up. . . .†He then returned to his speech, “Boys, I advise you to drink your own urine twice a day, those golden showers will cure what ails ya.†When he could sense that we were only listening to be polite, he became defensive, “I can see you don’t believe me. But you had better. I am a messenger from God.â€

Joseph spoke up, “What a coincidence. We are also followers of God’s messenger, Jesus.†That was the wrong thing to say, for the emperor grew agitated and exclaimed, “I’m #$%! Jesus Christ, the G——n messiah, Jesus isn’t coming back so you had better listen to me! If you don’t believe me, then get out my bus!â€

We groped for a diplomatic way to end our visit. “It was good to meet you, Emperor!†I said, as we exited the bus, befuddled by this strange encounter.

I turned to Joseph. “Well, I guess that attempt to be intentional about having relationships with people on the margins failed,†I said.

“We can’t make someone be our friend,†Joseph said, “if they don’t want a relationship.â€

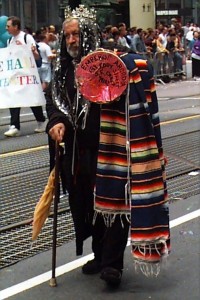

A few months later I ran into the emperor at the plaza downtown. Slumped over, sunburned and haggard and sitting in a wheelchair, he was hardly recognizable. Yet he was dressed impeccably, decked out in a costume crown and bright gold jewelry, wielding a royal amulet in his jittering hand. When I greeted him, he smiled, saying, “I’m doing better than ever, can’t you see? I was just going to get something to eat, would you like to join me?†Recalling our first encounter, I was taken aback by his friendliness. He insisted on buying me a strawberry shake. As he went up to pay, several tablets of methamphetamines fell out of his wallet onto the counter. Sitting in a booth across from me, he repeated, verbatim, the monologue from our first visit. I looked at him intently—his hands brown with filth, dirt caught in the creases of his worn skin. That mouth!—grotesque, toothless, and rotting, wildly chomping chicken sandwich. My stomach turned. Sputtering incoherently now, he was desperately trying to get through to me, as his spit and chicken sandwich landed on my face. I stared into his hazel green eyes, wondering what he was thinking and feeling inside. “Emperor Arcadia, what has it been like living by yourself in that bus all these years?â€

He paused dramatically. “It feels . . . lonely sometimes.â€

I pressed for more. “What do you do when you are lonely?â€

Subdued for a moment, he answered, “I lock myself in my bus for three or four days, or come down to this corner.†And then he quickly changed the subject. “I need to get a shower. . . Hey! Look at him, I’d like to have him on a chain to dominate. . . .â€

I racked my conflicted brain and heart to understand. I wondered, “Am I wasting my time with this man, or is he teaching me something about the compassion of Jesus?†When I told Joseph about my encounter with the emperor, we debated about engaging him further. We had previously written him off because we didn’t see much hope for change in his life. He also didn’t make us feel rewarded for our efforts. “Is an act of love only significant because of the change it produces? Or, can the meaning be in the act itself?†I pondered aloud. It seemed like God had brought the emperor back into our lives. While Joseph and I were discussing what to do, we thought of Jesus’ teachings about giving to others without expecting anything in return and the fact that God is kind, even to the ungrateful (Luke 6:35). We realized that, as followers of the Way, we were being invited to love the emperor despite his prickly hostility and highly unusual personal habits.

A few days later Joseph and I stopped by the emperor’s bus. More sedated, he expressed that he was glad to see us, and explained that he had just completed one of his “cycles of treatment,†which involved covering his entire body with menthol vapor rub followed by petroleum jelly, then taking a hit of methamphetamines. “We all have these bugs living in our bodies that are killing us. I’m slowly sweating them out,†he said. “This treatment forces the bugs from deep within the body to surface where they drown.†He explained how he then washes in a solution of vinegar, bleach, dish soap, and urine. “The whole process takes three days. Look at how young and fresh my skin looks now. Pretty good for being sixty-three years old.â€

“Emperor, is there anything we can do for you?†I asked.

“Well, I’m hungry and I haven’t eaten for days. My legs aren’t working too good so I can’t get to the store.†Handing us some money, he asked us to buy him an Italian sausage sandwich. “Make sure you get it with mayonnaise and provolone cheese—and buy yourselves sandwiches with my money too. They are very delicious.â€

As we ate the sandwiches together, two young men approached the bus. Dressed in leather pants and jackets, with their faces covered in sores and their hands black with grease, they looked like survivors of a nuclear holocaust. He handed these men, his drug suppliers, a wad of cash. “Keep the change, honey, for a personal favor I might ask of you later,†he said with a wink.

Along with other friends from our community we began visiting the emperor several times a week, bringing groceries, helping cut his hair or clip his toe nails, and cleaning up around his camp. Gradually he began to trust our friendship and revealed more about himself. His real name was Robert. Estranged from his family after years in mental institutions, he had moved west from Wisconsin. During the sexual revolution of the 1970s he was something of a celebrity in San Francisco’s gay club scene, hosting “naked pool†on Sunday afternoons at a popular bar South of Market where he would prance nude around the pool table exchanging fiery jabs with patrons. The club owner let him live in the basement of the building for many years. We learned that Emperor Arcadia was locally famous for crashing society balls, civic celebrations and parades, announcing himself, swathed in a velvet cape and crown, accompanied by his matching miniature poodles on leashes. As he got older and more peculiar, he lost his social currency and became more isolated.

The emperor’s health continued to deteriorate and by December he was confined to a wheelchair. In addition to this trouble, the owner of the property where he was squatting was taking legal action to have him removed. We advocated for the emperor with the health department and social services and pleaded with him to move into an assisted living facility. He pessimistically predicted that the apocalypse would come by the first of the year. “I’m going to kill myself on New Year’s Eve,†he told us, by mixing vodka with a fatal dose of Phenobarbital.

“I would be really sad if you chose to kill yourself,†I told him.

“Why should you care if I live or die?†he asked indignantly.

“Emperor, you are valuable to God and to the people who love you. We would miss you.â€

“Nobody has ever cared about me,†he replied bitterly.

“I’m really sorry you feel that way. After all the time we’ve spent together the past few months, I hoped that you might consider Joseph and me your friends.â€

. . .

At Christmas we decided to throw a party for the emperor, including his favorite foods and a birthday cake. I told him that I was going to bring my family along, so he would need to be on his best behavior. We could never predict what the emperor would say or do.

There was a full moon on that December evening when I knocked at the door to the emperor’s bus. He came out wearing an elegant purple bonnet, with freshly painted fingernails. A thin young woman, who we knew worked as a prostitute, lived in a trailer on the street nearby, joined us, along with one of her “clients.†We ate by candlelight serenaded by music from a transistor radio. The emperor declared that the food was delicious, a collection of favorite dishes he requested. After dinner my wife Lisa put candles on a cake. “Let’s sing happy birthday to someone who hasn’t celebrated their birthday in awhile,†I said. “Who could we sing happy birthday to?â€

Just then, beaming, our three-year-old son Noah blurted, “It’s Christmas, lets sing happy birthday to Jesus!â€

I panicked. The name Jesus was the worst thing I could imagine mentioning in front of the emperor, and I waited to see how he would react. Slowly, with a big toothless grin, he said, “Yes, let’s sing happy birthday to Jesus.†Under a clear and starry night the eight of us sang together—Lisa and me, a streetwalker and her john, a sixty-three-year-old transvestite, and three small blond children with red cheeks. As I helped the emperor back into his bus, he turned to me and said, “This was the best night of my life. Thank you!â€

. . .

We told the emperor that the following Sunday we would stop by with some friends to help move the bus and his belongings off the property to comply with the owner’s injunction. When we arrived Sunday morning Joseph and I knocked at the door of the bus. There was no response, but we heard a faint groaning from inside. We broke down the door and found the emperor collapsed on the floor, lying in a pool of his own waste. He tried to talk, and through his slurred speech, I deciphered that he wanted water. We sat him up, though he was semiconscious and weak, and gave him a drink. As we began to change his clothes and wash his body, what had happened slowly dawned on us—he had taken the Phenobarbital as planned. Searching quickly we found a few of the tablets scattered across the floor by a bottle of vodka. The rest of our group had just arrived when we called for an ambulance.

As the paramedics lifted him onto the gurney he pleaded for me to stay beside him. I rode along to the hospital in the back of the ambulance holding his hand.

At the emergency room after he was stabilized a nurse invited me into the examining room where I stood alone by his side. “Emperor,†I said, “it’s Mark.†With his eyes still shut he murmured, “I wanted to die. Why did you save my life?â€

I hesitated for a moment searching for words. “You are my friend and I care about you.â€

Agitated, with speech still slurred he asked, “But why do you care about me?†And then louder and more desperately he repeated, “Why do you care about me?â€

Slowly I lifted my hand and began to caress his bald head. “Emperor, we are all loved,†I said. Then I heard him snoring and watched his chest rise and fall with each belabored breath.

I stood there for a long time, praying, and thinking about this man who felt so isolated and lonely that it was impossible for him to imagine that anyone would care. Perhaps he was a living caricature of the feelings we all share—doubts about our worth.

When Joseph and I arrived at the hospital the next day he was wide awake and smiling. With hugs he greeted us like long-lost sons. He quickly handed Joseph some money and told him to go out and buy each of us a prime rib dinner to eat together. The hospital psychologist was anxious to meet me and discretely invited me into her office. I held the keys to his bus and kept all his legal and personal papers and gave her as much of his life story as I had pieced together through our conversations. As I shared what I knew I had the strange realization that, although I had only known the emperor for six months, I was closer to him now than anyone else alive.

After the interview the doctor curiously asked, “What exactly is your role in the neighborhood?†I explained that Joseph and I were part of a small church community trying to imitate the example of Jesus by making friends with lonely people. “That sounds like the kind of church I would love to join,†she replied.

. . .

Even now as I retell this story I am drawn back into the sights and smells and complicated emotions I felt during that time. I realize there is unique absurdity to the characters and situation—two idealistic young men and their experiment in friendship with an eccentric old man with a death wish. By telling this story I’m not suggesting that everyone could or should make friends with someone like the emperor. What I do know is that I feel alive when I am testing the limits of my own boundaries– finding a source of love that is greater than my own and discovering beauty in unexpected places.

Conversation

Credibility. What kind of reputation does the Way of Jesus have with the people in your community? How might this be changed or improved by people who take Jesus more seriously as an example and guide?

An Experiment in Friendship. What were your feelings or thoughts as you read about the emperor? What did the details and ambiguities of the story provoke in you?

Experiments

Be open to the peculiar. There is likely someone in the periphery of your relationships who is lonely or peculiar. Quite often the public services and support offered to people living with mental illness are inadequate. In the gospels these kinds of people were often drawn toward encounters with Jesus and his disciples. Go out of your way to cultivate a friendship with such a person—in partnership with a friend who can help you navigate the relationship.

Teach a child to care. You may wonder if it is safe for children to be around unstable or addicted people. If there is adequate guidance and supervision it can be helpful to introduce children to the more sobering realities of our society– and they may be less likely to have an unhealthy fascination with illicit activities if they learn to care about people in those circumstances. Take a child with you to visit a shelter, prison, soup kitchen or assisted living facility. Kids learn to be compassionate by watching their parents and elders care for the needs of others.